The Politics of Empathy

Musings on words, violence and the world we want...

In the light of Charlie Kirk’s death—and the wave of conversation it has sparked about political violence—I’ve been reflecting on how powerful words and ideas can be. I’ve been mulling over the ways in which harm is understood and constructed in this country, how often fear is conflated with physical harm and what happens when dangerous ideas are platformed.

By the way, these are incomplete thoughts, but they’re the beginning of something deeper that I’d like to explore…

First and foremost, I want to share that I believe deeply in the power of love, compassion, and repair. I am an abolitionist. That means I’m committed to building a world where compassion is not the exception, but the norm. I’m equally committed to pushing back against the growing ideology that normalizes apathy and even cruelty. It is wise to center the voices of those who are most impacted by the rhetoric that Charlie Kirk spread at this time.

Short Video: Monique, BlackbeltBabe

The Politics of “Anti-Empathy”

As the Trump administration positions Kirk as a martyr of sorts, many find it hard to have sorrow. The cruel irony is Kirk himself ridiculed empathy. He dismissed it as a “new age concept” that weakens logic, framing it as a “dangerous” liberal trap. His words weren’t random. His rhetoric was designed to appeal to young men, particularly Gen Z and Gen Alpha, who are increasingly leaning conservative compared to their female peers. By redefining empathy as weakness and elevating cruelty as strength, Kirk built a cultural code. It wasn’t just vapid; it was strategic. It numbed his audience to suffering while fostering an identity rooted in outdated and hyper-masculine ideals. His playbook also served as a money making machine, capitalizing off of the despair of impressionable, lonely adolescents.

But to relegate these ideas and ideological strategies to the far right is naïve. Even in cities considered liberal, such as San Francisco, Seattle, Los Angeles, I’ve noticed the erosion of empathy. For decades, these places nurtured a culture that recognized poverty, addiction, and homelessness as systemic issues, not personal failings. We knew the rent was too damn high. We knew addiction was a kind of quicksand. We knew many unhoused people came out of foster care, or were escaping domestic abuse, or worse. Whereas sympathy is often thought of as paternalistic—a looking down on someone else in pity—empathy acknowledges our inextricable connection as humans.

And yet, in the past three years, I’ve noticed a coordinated push to harden public opinion—to prepare people for more cruelty. Political consultants like Sam Singer, and elusive social media accounts like Bay Area State of Mind, saturated feeds with images of theft and sideshows. These posts disproportionately showcased Black and brown youth and equated property damage with physical violence.

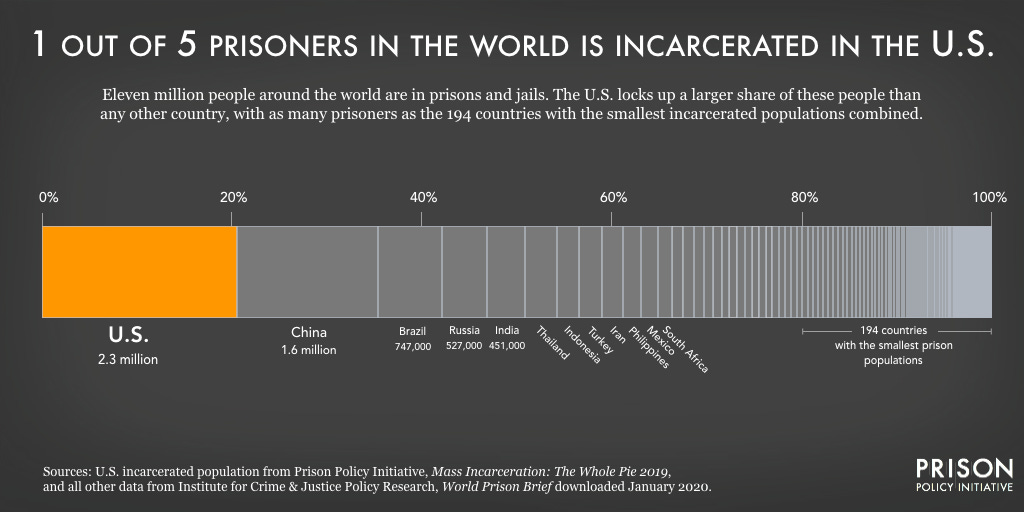

The result? Even lifelong Oaklanders started to feel their city was more dangerous than ever, despite the reality: violent crime has dropped significantly in cities like Oakland, Chicago, and Baltimore. The perception of danger, constantly stoked, became more powerful than the truth. People stopped walking in their neighborhood. Everyone spoke poorly of Oakland. We lost trust in our community, even coming out to vote against then mayor Sheng Thao. Folks began to cling to the idea of more police, prisons and tougher sentences as a solution (even though the United States incarcerates more people per capita than any other wealthy nation on earth, and yet we’re one of the most violent nations).

Which brings me back to Kirk.

His final words were about gang violence, framed in contrast to mass shootings in the U.S. overall. This wasn’t accidental. Instead, it was another rhetorical attempt to redirect legitimate alarm about our gun violence crisis toward people of color in inner cities, while minimizing the very real threat of white supremacist mass shootings.

These logics (conflating property damage in expensive cities with bodily harm or conflating marginalized communities with danger) are warped. They destroy empathy, making cruelty seem more rational. Maybe it’s time to stop platforming them all together. Maybe we should sunset debate bro culture, especially if we’re “debating” hate speech.

Short Video: Imani Barbarin, crutches_and_spice

Why This Matters to Me

I’ve been experimenting for months with ways to write about these connections between creativity/art and leftist organizing.

The right has been wildly successful in building a base with their stories, their codes for how to be “a real man,” and we on the left need to get better at educating the public, especially young people.

This isn’t abstract for me. I spent nearly a decade working with incarcerated youth, mostly Black, brown, and poor white boys, who had both experienced and caused harm. When their struggles were ignored, it set the stage for the broader cultural crisis we’re in now.

And now, we have figures like Kirk, amplified by debate culture, spreading ideologies that should never have a megaphone. And those ideologies don’t disappear just because of Kirk’s killing.

The Task Ahead

If cruelty can be normalized through language, then compassion can too. If rhetoric can numb us, then art and organizing can reawaken us. Words matter—but only if they’re tied to the deeper work of repairing, educating, and organizing for a world rooted in justice and care.

Sharing this!!