SINNERS and Genre As Capture

First Thoughts About The Box Office Sensation (NO SPOILERS)

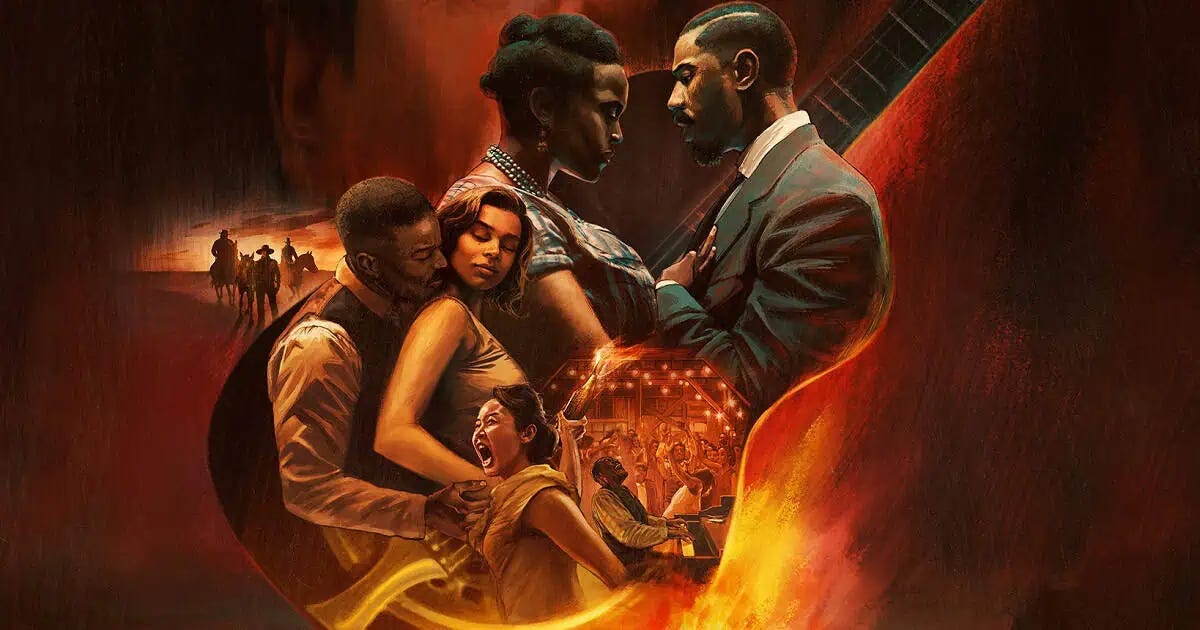

I have a lot to say about Ryan Coogler’s new film, Sinners. Never mind the fact that he’s from Oakland, where I currently reside. The Town, and the country, is buzzing. Why? Sinners is the kind of film that stays with you long after you leave the theater. It pulls you into a world you wish you could stay in a little longer—even with bloodsuckers lurking in the shadows.

Set in the 1930s during the era of sharecropping (a system that essentially reinvented slavery through debt), Sinners follows Sammie (played by Miles Caton), a young Mississippi musician chasing success. He dreams of seeing the world like his Chicago cousins, Smoke and Stack (played by Michael B. Jordan). He hopes music will be his ticket out. Instead, it is a way in.

Fast forward to the final shot, which is stunning: a birds-eye view of the cotton fields. Smoke, wearing a blue hat, symbolizes family and love. Stack, in a red hat, represents money and survival at any cost. Sammie sits in the backseat, caught between the two. It's a classic good vs. evil setup, but it goes deeper, capturing the tension Black artists often feel: how to stay true to their roots while surviving in a world that demands they sell parts of themselves to succeed. Now, let’s discuss the vampires…

Sinners’ vampires aren't just villains; they are metaphors for how the music industry feeds off Black culture, draining its life and repackaging it for profit. The Vampire King, Remmick (a thousand-year-old Irish folk singer) isn’t random. He reflects real aspects of American music history that have shape-shifted over time. (If you know the roots of "The Rocky Road to Dublin," you’ll catch the deeper meaning.) As always, Coogler’s villains are never exactly what they seem. They feed on our fears.

In a recent Democracy Now interview, Ryan Coogler described Sinners as a "cinematic gumbo.” He’s blending elements that might seem unrelated into something powerful. The film was also inspired by his late uncle, who passed away while Coogler was making Creed. As a tribute, Coogler built the film’s world around the Blues. Through his research into the genre, he also uncovered deeper truths about the music industry.

I was surprised when Coogler made an important point: the very concept of "genre" is rooted in racism — designed to exclude Black musicians from profiting equally with white counterparts. This realization explains why Sinners constantly plays with genre.

Something else that’s fascinating to me: the Southern lore of Robert Johnson, who was rumored to have "sold his soul to the devil" to gain Blues talent. In reality, Johnson’s success was the result of intense practice, but because art feels so spiritual, people often fail to see the hard work behind it. Making art is labor. Taking this old tale and turning it on its head is brilliant. It shows that Coogler knows how to follow a vision.

Others believed in his vision too. Coogler speaks openly about how essential his wife, Zinzi Evans (Co-producer), has been to his creative success. Their partnership, built on mutual support and respect, was crucial to making this project happen. In my opinion, this raises bigger insights about the invisible labor women artists often take on to support artistic output, whether in homes, relationships, or behind the scenes of your favorite sets, and what men can do to better recognize and amplify that labor.

Finally, Coogler mentions the deal he made with the big production companies to get Sinners to the box office. While there’s been a lot of hype, he’s a little surprised by the hubbub. He hints that, for once, he was able to negotiate fair compensation, something that hasn’t always happened for him, even though his films have made billions—for other people. This matters because Coogler is the kind of artist who gives back, and owning more of his work will only increase his positive impact.

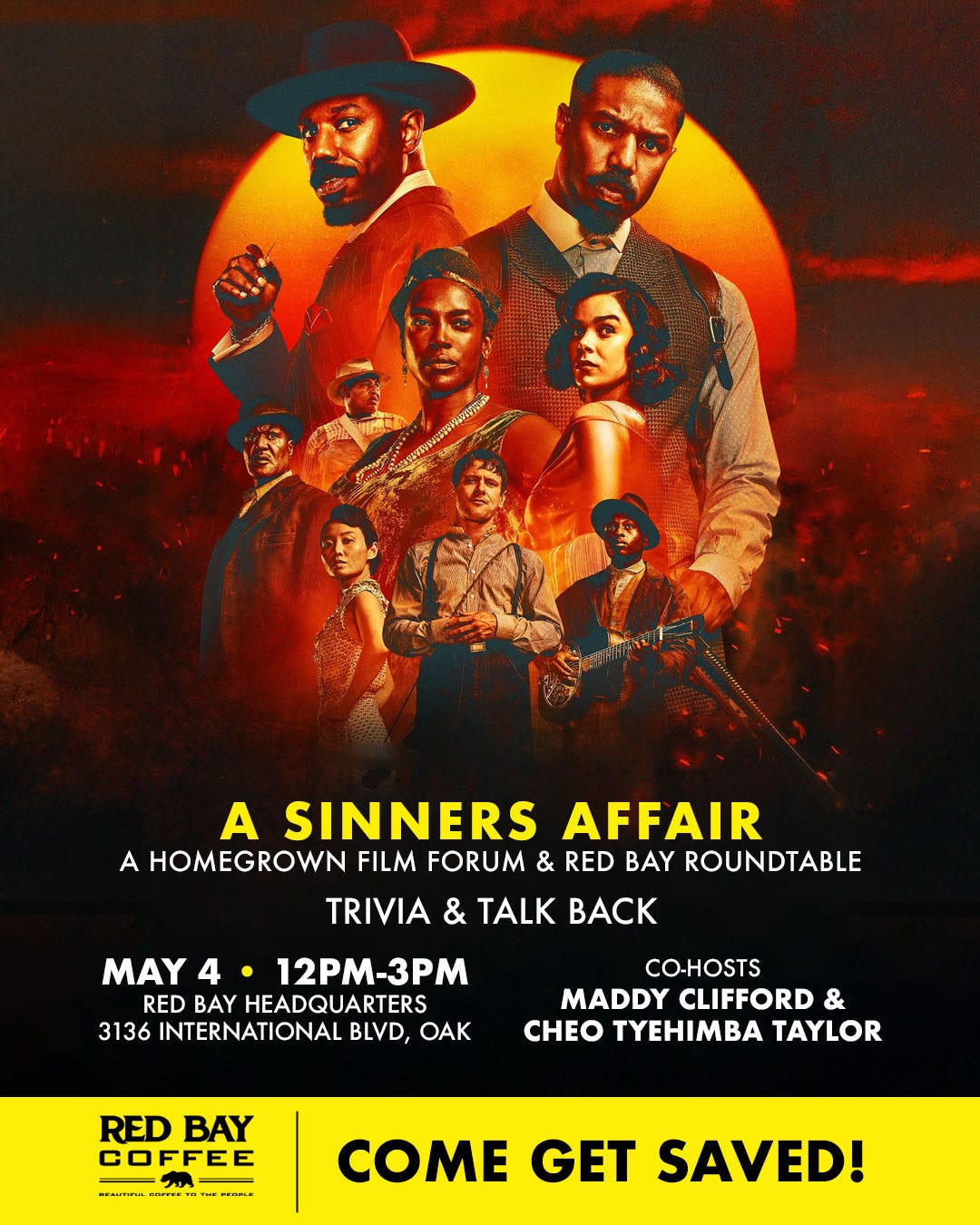

Wish I could go! Looks like you have yourself a crowd!