Grief Speaks When Artists Engage

Grief is an invitation — to connect, to reflect, to resist, to create.

If I could choose just one emotion to encompass the political and cultural climate in the United States right now, it would be grief.

Not the neat, black-dressed, funeral-version of grief. I’m talking about the messy, complex, slow-burning, all-consuming grief that lives just under the surface.

The kind that feels more like opening Pandora’s box than anything else. The box they tell you not to open, ever. Because once you do, everything unravels. Pain. Chaos. Vulnerability. Fear…Possibility?

And yet, here we are. The box is open. The grief is pouring out.

In a world where politicians wage war on the working class, where people are dying under the weight of systemic violence (in Palestine, in the U.S., in countless unseen places) how do we live while carrying that knowledge?

Grief becomes tangible when you realize that the systems around us are not just flawed, but actively harming the most vulnerable. Migrants are being kidnapped before our very eyes. Yet somehow, we're expected to go to work, pay bills, post something online, and move on as if that’s normal.

But here’s the thing: Grief isn’t a weakness. It's not something to suppress, hide away or silence. It’s one of the most powerful emotional forces we have, especially as artists.

Because inside of grief, like inside of that mythical Pandora’s box,

there’s also POWER.

Getting Personal: Sacred Realizations in Jamaica

Grief and I go way back.

I didn’t always have a name for the gnawing feeling of grief. At first, I had experiences. One experience was losing a parent to violence. My father’s life was taken when I was a teenager. It happened in Seattle. It was a brutal. And back then, I didn’t know how to process it, let alone how to face the pain. His entire existence was reduced to a news article. How could someone do something so violent to someone else? Very few folks around me could relate either. Who could I talk to? I usually stayed silent. I made myself busy going through the motions, completing finals and filling out college applications. I wanted to escape. But to where? I was detached and depressed. Just don’t let this ruin your future, I told myself as I floated through life like a piece of debris from a fire.

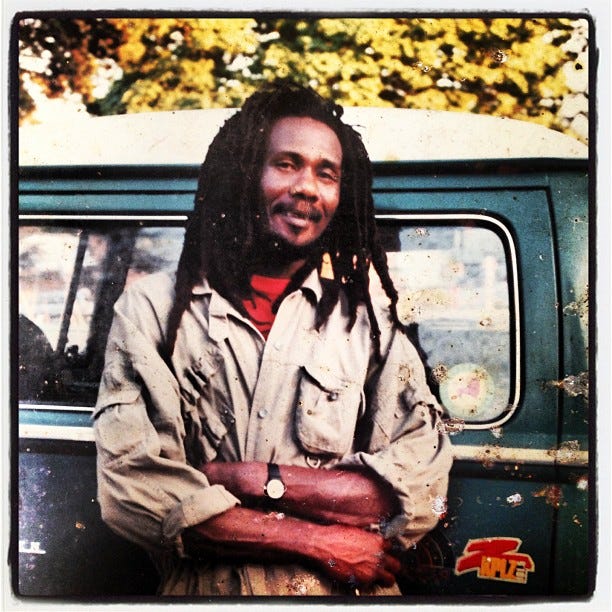

(A snapshot of father, Raymond “Ras Bongo Flyah” Lindsay before migrating to the U.S. in his thirties.)

But then, my mom surprised me one day with a ticket to Jamaica for the entire summer — to reconnect with a part of my cultural identity I knew very little about.

When most people think of Jamaica, they think of white-sand beaches and all inclusive resorts. But there’s so much more to my father’s island. Jamaica is its people. Unfortunately, very few tourists engage with the culture of Jamaica; most bask in the paradise created by corporate giants like Sandals resort. How many people travel to Jamaica without ever learning about the complex history? How many know that 90% of Jamaicans can’t access the beach at all due to the privatization of land? How many tourists tap in to how and why folks are grief-stricken? Who sees the unruliness blossoming like speckles of coral flowers dotting the historic Blue Mountains?

I ended up living in Spanish Town during my stay, just outside Kingston for three months. I was a teenager, just discovering feminism, journaling on the rooftop while my oldest auntie — the family matriarch — kept me almost exclusively indoors “for my safety” as the sounds of the most beautiful music I’d ever heard wafted from stereo speakers and the sweltering heat felt heavy (its own kind of lockdown).

That year, Sizzla’s “Solid As A Rock” dropped. I sucked on bag juice that stained my lips orange or ate delicious curry chicken and dumplings. I learned the latest dances (there was a new dance every week and the whole island learned it) and got to know my family members better.

My cousins, tall men with fashion sense, high cheekbones and dark skin, told me stories about my dad. Their eyes would well with tears, their faces would sometimes grimace in anger and despair too. One thing was for certain: I was not alone in my grief. In fact, in 2005, the year I graduated from high school, the tiny island of Jamaica experienced the highest per capita murder rate in the world. Grief was everywhere.

It lurked in dark corners and made us sweat. It slept beside us in bed, flashed on the TV screens and ricocheted through our dreams. We’d dance about it, sing about it, joke about it even. If, like Rumi wrote, “the wound is the place where the light enters you” then we were full of light. Grief was a reminder that no matter how fast Jamaica tried to escape the cruel history and after-affects of chattel slavery, it couldn’t get away without a fight. And we were constantly fighting.

(Visiting my father’s grave in St. Thomas, Jamaica years later.)

Poverty is violent in and of itself, but much like resistance to enslavement, there is a long and beautiful legacy of pushing back against the suffocating nature of colonization.

One day, I got sidetracked as I was walking in town with family. I ended up on a lonely street, which left me in direct eyesight of prison windows just above a massive concrete gate. I suddenly heard the sound of men screaming from the cement structure, their arms outstretched like branches in the sunlight, reaching out to me. It was nerve wracking. It was strange. Was this where the man who’d killed my father ended up? Somewhere like this? Rotting. Reeling. What good would that do to me? Where would my grief go now?

It went into my pen and never left.

My experience in Jamaica opened up a pandora’s box that has never closed.

I’ve since traveled to JA eight times and I’ve even attained dual citizenship. I’ve learned more about Caribbean history including the the urgent, multigenerational and vibrant grieving-cultural practices that make the region hum with power.

This discovery-process has brought me a deep sense of purpose. I became an abolitionist. In fact, my grief story came full circle when the man who took my father’s life died by suicide in a barbaric ICE detention facility.

I have chosen to turn the endless agony of the Prison Industrial Complex into a promise to interrupt violent systems that only increase harm. I know what keeps us safe: education, housing, healthcare and community. And that’s why our enemies want us isolated, why they defund access to care and spread “tough on crime” propaganda as a soulless answer to cycles of violence.

Instead of wallowing in despair, I faced grief and let it educate me. I took action, teaching creative writing, performance and conflict resolution in the townships of South Africa, in Uganda and Argentina and to incarcerated people in the United States. I’ve used art to support folks in alchemizing their own grief, especially children. And I’m just getting started.

Jamaica taught me something I’ll never forget: Grief doesn’t have to isolate us.

It can connect us.

Grief as Creative Fuel

Grief is its own kind of fuel. It doesn’t always explode. It often lingers. It weaves itself into our hands, our voices, our brushstrokes, our poems. One of the greatest myths we’ve been taught is that grief is something to “get over.” That healing is linear. That if we’re strong enough, we’ll bounce back. But that’s not how it works.

I’ll never be “over” the loss of my parent to violence. And I won’t pretend that grief made me stronger. Sometimes, grief pulls you under water, holds you back, distorts your reality and it takes years to recover. Grief can also disconnect you from the rhythms of a world and tether you to social norms that value productivity over facing pain or celebrating survival.

But here's the truth I hold onto: we heal in community.

And we can transform through creation.

In moments when grief feels too heavy to carry, cracks do also appear: a conversation with a family member or friend, making piece of art that makes us feel seen, a shared moment of stillness, a protest chant that feels like prayer or a revelation in organizing work. Those are the openings. And from them, something new can grow.

A Prompt (If You Choose to Accept It)

Personify Your Grief

One of my favorite writing exercises are around personification. It’s the act of giving human qualities to something non-human. Basically, it is a way of breathing life into abstract feelings, complex feelings, feelings that may take a lifetime to unlock. Personification is a magical poetic device.

So here’s a creative prompt for you:

If your grief (the emotion) were personified, who would he/she/they be?

What’s their story? How do they speak?

What do they wear? What’s their favorite food?

What do they want from you? How do they move through the world?

What do you want from them?

Still feeling stuck? Make a list of action-words that make us human and attribute them to grief:

Examples: Hide, Haunt, Cry, Fly, Ask, Tremble, Spin, Crouch, Grow, Laugh, Crouch.

In this moment of so much collective pain, let’s not close the box. Let’s open it fully. Let it breathe. Let it rage. Let it grieve. And let’s alchemize it — not into something neat or perfect, but into something true.

Because that’s where the art lives. In the cracks. In the openings. In the waves.

And from that, something new can bloom.

To all the artists grieving out there — keep creating.

The world needs your voice.